Psychology: Learning and Memory

Understanding Conditioning Processes, Memory Systems, and the Complexities of Remembering and Forgetting.

Happy Friday!

Insight Trunk is a free lifetime library—a modern replacement for outdated encyclopedias. From Monday to Saturday, we deliver a 10-minute read on a specific subject, with fresh topics each week. Two years later, we revisit each theme with updated insights from our archives—so you’ll never miss a thing. You can unsubscribe anytime using the link at the bottom of this newsletter.

Today, we explore how we acquire and retain knowledge: Learning and Memory. We’ll cover essential processes like classical and operant conditioning. Our focus then shifts to memory, examining different models (short-term, long-term) and common ways we forget and reconstruct past events. Get ready to train your brain!

🧑💻 In this week’s edition: Psychology

Monday - Foundations and Intelligence

Tuesday - Motivation and Emotion

Wednesday - Personality and Dark Triads

Thursday - Social Psychology and Behavior

Friday - Learning and Memory

Saturday - Disorders and Treatment

Question of the day

What term is used when an organism learns to associate a voluntary behavior with its consequences?

Let’s find out !

Learning and Memory

Let’s break it down in today discussion:

Associative Learning: Conditioning Principles

Learning Beyond Association: Cognitive and Observational Processes

Architecture of Human Memory Systems

Memory’s Imperfections: Forgetting and Reconstruction

Read Time : 10 minutes

🔄 Associative Learning: Conditioning Principles

Learning, defined as a relatively enduring modification in behavior resulting from experience, is fundamentally explained through associative learning, which includes classical and operant conditioning. Classical conditioning, rooted in the work of Ivan Pavlov, involves the learned association between two stimuli. This process pairs a previously neutral stimulus (NS), such as a tone, with an unconditioned stimulus (UCS), such as food, which naturally elicits an unconditioned response (UCR), like salivation.

Through repeated pairings, the NS transforms into a conditioned stimulus (CS), capable of eliciting a conditioned response (CR) (salivation) even in the absence of the UCS. This type of learning primarily affects involuntary, reflexive behaviors and is central to understanding phobias and emotional responses. For example, a dog learns to associate the sound of a can opener (CS) with being fed (UCS).

In contrast, Operant conditioning, largely developed by B.F. Skinner, focuses on the association between a voluntary behavior and its consequences. Behaviors followed by a reinforcer (e.g., a reward) are strengthened and become more frequent, while behaviors followed by a punisher are weakened and become less frequent. This process demonstrates how consequences actively shape and maintain goal-directed actions in an organism.

Get a more thorough explanation in this video.

🧠 Learning Beyond Association: Cognitive and Observational Processes

Beyond the direct associations formed through conditioning, significant forms of learning involve cognitive mediation and social observation. Observational learning, extensively researched by Albert Bandura, emphasizes that individuals can acquire new behaviors, attitudes, and emotional reactions by simply watching others, a process often termed modeling. This learning is distinct from classical or operant conditioning because direct reinforcement is not required for the learning to occur.

Bandura identified four necessary cognitive processes for effective observational learning: Attention (the learner must focus on the model’s behavior), Retention (the ability to remember the observed behavior), Reproduction (the capacity to physically perform the behavior), and Motivation (the incentive or reason to perform the learned action). A classic example is the Bobo doll experiment, where children who observed an aggressive adult model later imitated the aggressive behavior.

More broadly, cognitive learning theory focuses on the role of internal mental processes such as insight, thinking, and problem-solving. Concepts like latent learning, which is knowledge acquired without any obvious reinforcement and only demonstrated when an incentive is provided, highlight the brain’s capacity to form mental representations. Another example is insight learning, a sudden and often novel realization of the solution to a problem, suggesting an abrupt cognitive restructuring rather than gradual trial-and-error.

This video is your next step to mastering the topic of social learning theory.

💾 Architecture of Human Memory Systems

Memory is the cognitive process responsible for encoding, storing, and retrieving information. The prevailing model for understanding its structure is the Three-Stage Model of Memory (or the Atkinson-Shiffrin model), which posits that information must pass through distinct memory stages to become permanently stored. The initial stage is sensory memory, which briefly holds an exact replica of sensory input for a fraction of a second, such as the visual image of a camera flash.

Information attended to from sensory memory moves to Short-Term Memory (STM). STM has a severely limited capacity, typically retaining only about seven plus or minus two discrete items of information, and a brief duration, lasting approximately 20 to 30 seconds without active rehearsal. Its primary function is to temporarily hold and process current information. The concept of Working Memory is often used interchangeably with or as an extension of STM, emphasizing its active role in manipulating information.

Through processes like elaboration and consolidation, information can be transferred from STM to Long-Term Memory (LTM). LTM is characterized by its virtually unlimited capacity and relatively permanent duration. LTM is functionally sub-divided into Explicit (Declarative) Memory, which requires conscious recall (e.g., facts and events), and Implicit (Non-declarative) Memory, which occurs without conscious awareness (e.g., procedural skills like riding a bike, or classical conditioning effects).

Explore additional perspectives about how memories are created and stored by watching this video.

💔 Memory’s Imperfections: Forgetting and Reconstruction

While memory is a critical cognitive function, it is inherently susceptible to failure and distortion. Forgetting—the inability to retrieve previously stored information—is explained by several theories. Decay Theory suggests that memory traces in the brain naturally fade or weaken over time if they are not periodically accessed and rehearsed. In contrast, Interference Theory posits that forgetting occurs because the learning of certain items hinders the retrieval of other information, which can be proactive (old information blocks new) or retroactive (new information blocks old).

Crucially, memory is not a passive recording but an active, reconstructive process. When information is retrieved, the brain uses logical inferences, existing knowledge structures (schemas), and external cues to fill in any gaps. This reconstruction process makes human memory vulnerable to systematic errors, as documented by cognitive psychologist Elizabeth Loftus.

One profound example of this vulnerability is the misinformation effect, where a person’s recollection of an event becomes less accurate due to exposure to misleading information received after the event has occurred. For example, suggestive questioning can alter an eyewitness’s memory of a crime. This phenomenon demonstrates that the act of remembering is fluid and that retrieved memories, even those held with conviction, are not necessarily perfect representations of past reality.

Learn more about what we discussed by watching this video!

Summary

Associative Learning: Conditioning

Learning is defined as a relatively lasting change in behavior that results from experience.

Classical conditioning involves learning to associate two stimuli, where a neutral stimulus eventually elicits a conditioned response through pairing with a natural one (e.g., Pavlov’s dogs).

This type of learning primarily affects involuntary, reflexive behaviors and helps explain emotional responses like fear.

Operant conditioning involves associating a voluntary behavior with its consequences.

Behaviors are strengthened by reinforcement (rewards) and weakened by punishment to control future actions.

Cognitive and Observational Learning

Observational learning, studied by Bandura, allows individuals to learn new behaviors by simply watching and modeling others, without needing direct rewards.

This process requires four cognitive steps: attention (focusing on the model), retention (remembering the behavior), reproduction (being able to perform it), and motivation (wanting to perform it).

Cognitive learning emphasizes internal mental processes like thinking and problem-solving, rather than simple stimulus-response associations.

Examples include developing a cognitive map (mental representation of an environment) or insight learning (a sudden realization of a solution).

The Three-Stage Memory Model

Memory is the system used for encoding, storing, and retrieving information.

The Three-Stage Model proposes that information sequentially moves from sensory memory (brief, fleeting storage of sensory input).

Information moves to short-term memory (STM), which is limited in capacity (about 7 items) and duration (about 20-30 seconds).

Through active processing, information is transferred to long-term memory (LTM), which has a vast, relatively permanent storage capacity.

LTM is divided into explicit (conscious facts and events) and implicit (unconscious skills and conditioning) memory types.

Forgetting and Memory Fallibility

Forgetting can be explained by decay theory (memory traces fading over time) or interference theory (new or old information blocking retrieval).

Memory is inherently a reconstructive process, meaning the brain fills in gaps with logic and existing knowledge (schemas) during retrieval.

This reconstruction makes memory prone to systematic errors and distortions.

The misinformation effect shows that exposure to misleading post-event information can significantly alter the accuracy of an individual’s recollection of an event.

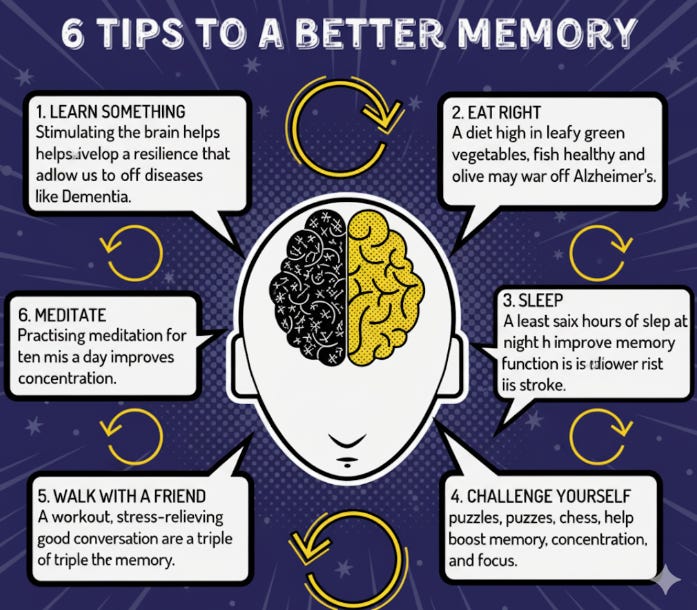

Improve your memory and study habits.

Use Retrieval Practice: Actively test yourself by recalling information from memory rather than passively rereading your notes, which strengthens long-term retention.

Employ Elaborative Rehearsal: Connect new concepts to existing knowledge or personal experiences to encourage deeper processing and better encoding into LTM.

Space Out Your Learning: Instead of cramming, distribute your study sessions over several days to consolidate memories more effectively (spacing effect).

Chunk Information Effectively: Group large sets of disorganized data into smaller, meaningful units to overcome the capacity limit of short-term memory.

Prioritize Quality Sleep: Ensure sufficient rest after learning new material, as sleep is crucial for the consolidation and stabilization of newly formed memories.

Answer of the day

What term is used when an organism learns to associate a voluntary behavior with its consequences?

Operant conditioning.

Operant conditioning, central to the work of B.F. Skinner, is a type of learning where behavior is strengthened if followed by a reinforcer (reward) and weakened if followed by a punisher. This process demonstrates how consequences shape and control voluntary actions.

That’s A Wrap!

Want to take a break? You can unsubscribe anytime by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of your email.