Game Theory: Solving Simultaneous Games

Finding Stability: Calculating Pure and Mixed Strategy Nash Equilibria in simultaneous-move games.

Happy Tuesday!

Insight Trunk is a free lifetime library—a modern replacement for outdated encyclopedias. From Monday to Saturday, we deliver a 10-minute read on a specific subject, with fresh topics each week. Two years later, we revisit each theme with updated insights from our archives—so you’ll never miss a thing. You can unsubscribe anytime using the link at the bottom of this newsletter.

Today, we dive into finding solutions for games where decisions are made concurrently. We’ll master the Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium—the stable outcome where no player regrets their choice—and learn how to calculate mixed strategies when pure solutions are elusive, providing powerful prediction tools.

🧑💻 In this week’s edition: Game Theory

Monday - Foundations and Representation

Tuesday - Solving Simultaneous Games

Wednesday - Solving Sequential Games

Thursday - Games with Incomplete Information

Friday - Dynamic and Repeated Games

Saturday - Key Applications and Concepts

Question of the day

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, what is the action profile where neither player wants to unilaterally deviate?

Let’s find out !

Solving Simultaneous Games

Let’s break it down in today discussion:

The Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium

Determining Mixed Strategies and Their Probabilities

Analyzing the Prisoner’s Dilemma and Coordination Games

Examining Limitations and Assumptions of the Nash Equilibrium

Read Time : 10 minutes

⚖️ The Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium

The Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium (NE) is the foundational solution concept for analyzing strategic interactions, particularly in simultaneous-move games represented by the Normal-Form matrix. It defines a state of mutual best response from which no single player has an incentive to unilaterally deviate.

Formally, a strategy profile (s1*, s2*, … , sn*) is a Nash Equilibrium if, for every player i, their chosen strategy si* maximizes their payoff given that all other players j are playing their specified equilibrium strategies sj*.

The practical method for finding a pure NE involves identifying each player’s best response to every potential action of their opponents. For Player 1, one must determine which of their strategies yields the highest payoff given Player 2 chooses a specific action. This process is then repeated for Player 2, mapping their best responses to Player 1’s actions.

A Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium is an outcome where the chosen strategies are simultaneously a best response for all players. Consider a simplified competition where two firms can choose to “Advertise” or “Not Advertise.” If the cell where (Advertise, Advertise) is the mutual best response, it represents a stable outcome because if either firm unilaterally switches to “Not Advertise,” their payoff would decrease.

Learn more about Nash Equilibrium in just 5 minutes by watching this video!

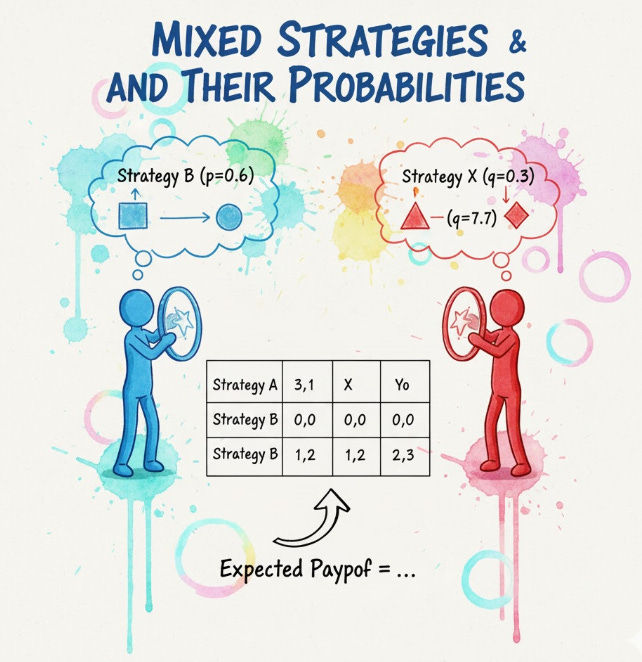

🎲 Determining Mixed Strategies and Their Probabilities

In numerous games, a stable equilibrium does not exist when players are restricted to pure, deterministic strategies. In such scenarios, the concept of Mixed Strategy Nash Equilibrium (MSNE) becomes essential.

A mixed strategy is a probability distribution over a player’s available pure strategies. Instead of choosing one action with certainty, the player randomizes their choice according to this distribution. The rationale is to introduce uncertainty, preventing the opponent from exploiting a predictable pattern. Games like “Matching Pennies,” where any pure strategy pair leads to one player wishing to deviate, necessitate a mixed strategy solution.

The MSNE is defined by a set of probabilities such that each player’s chosen mix makes the other player indifferent between all of their own pure strategies that are played with a positive probability. For two players, Player A chooses probability p for strategy s1 and 1-p for strategy s2. Player B then sets q for t1 and 1q for t2. The equilibrium values of p and q are found by setting the expected utility (EU) of Player B’s pure strategies equal: EUB(t1) = EUB(t2).

The significance of mixed strategies is codified in Nash’s Theorem, which proves that every finite game—a game with a finite number of players and a finite number of strategies—possesses at least one Nash Equilibrium, whether it be in pure or mixed strategies. This guarantees that a robust, stable solution can always be found for this class of games.

For a deeper understanding, check out this video.

🧩 Analyzing the Prisoner’s Dilemma and Coordination Games

Two canonical simultaneous-move games—the Prisoner’s Dilemma and Coordination Games—provide profound insights into the conflict between individual incentives and collective outcomes as defined by the Nash Equilibrium (NE).

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is the most famous illustration of how individual rationality can lead to a Pareto-inefficient outcome. In this game, each player has a dominant strategy (e.g., “Defect”), which, when played by both, results in a unique NE where both players are worse off than if they had cooperated. The equilibrium (Defect, Defect) is stable because neither player can unilaterally switch to “Cooperate” without reducing their own payoff, even though the Pareto-optimal outcome is (Cooperate, Cooperate) .

Conversely, Coordination Games demonstrate scenarios where the strategic challenge is not conflict, but rather selecting one common best outcome from several. These games feature multiple Pure Strategy Nash Equilibria. For instance, in a game where two firms must choose a standard (e.g., technology A or B), (A, A) and (B, B) might both be NEs. The problem is thus coordinating on which stable equilibrium to choose, often leading to potential losses if players fail to converge on the same strategy.

These two archetypes highlight the spectrum of strategic challenges. The Prisoner’s Dilemma illustrates the failure of self-interest to maximize social welfare, demonstrating the need for enforcement or repeated interaction to achieve cooperation. Coordination Games, conversely, demonstrate the limitations of the NE as a predictive tool when multiple stable, yet often unequally preferred, outcomes exist.

This video will explain The Prisoner’s Dilemma in One Minute.

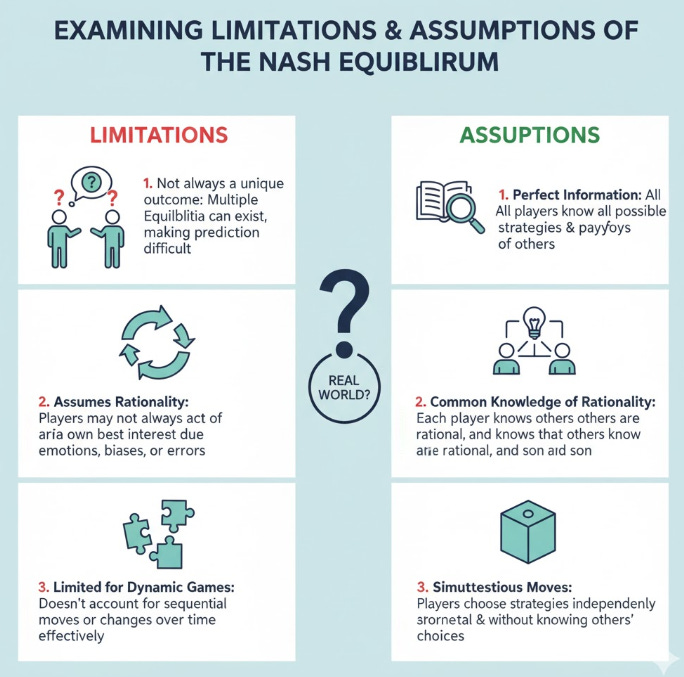

🛑 Examining Limitations and Assumptions of the Nash Equilibrium

While the Nash Equilibrium (NE) is a cornerstone of game theory, its applicability and predictive power are predicated on several restrictive assumptions that must be acknowledged. Violations of these assumptions can lead to observed behaviors diverging from theoretical predictions.

The NE concept fundamentally assumes perfect rationality—that all players possess unlimited cognitive ability to analyze the game structure and flawlessly compute the strategy that maximizes their expected payoff. In real-world contexts, players face cognitive limitations, time constraints, and computational complexity, often leading them to rely on heuristics or simplified decision rules, which invalidates the assumption of optimizing behavior.

A stronger, related assumption is the common knowledge of rationality (CKR). This means that Player A knows B is rational, A knows B knows A is rational, and so on, ad infinitum. If a player suspects the opponent is not fully rational, or if the opponent might not be aware of the game structure itself, the predictive validity of the NE diminishes, as optimal strategy depends on beliefs about the opponent’s thinking process.

Furthermore, the existence of multiple Nash Equilibria poses a limitation on the concept’s practical utility. When a game yields several stable outcomes (as in coordination games), the NE alone cannot predict which outcome will prevail. The model provides a set of possibilities but offers no mechanism for equilibrium selection, requiring supplemental concepts like focal points or refinement techniques.

Summary

The Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium (NE)

The Nash Equilibrium is the primary solution concept for simultaneous-move games, representing a stable outcome.

A strategy profile is an NE if no single player can improve their payoff by unilaterally changing their action.

Finding the NE involves identifying each player’s best response to all of the opponents’ possible strategies.

An NE occurs where all players’ best responses coincide, creating a mutual, self-enforcing choice.

The Necessity of Mixed Strategies

Many simultaneous games, particularly those with purely opposing interests (like Matching Pennies), lack a Pure Strategy NE.

A mixed strategy involves a player choosing a probability distribution over their available pure actions rather than one deterministic action.

The equilibrium probabilities are calculated to make the opponent indifferent between their own pure strategies.

Nash’s Theorem guarantees that every finite game has at least one equilibrium in pure or mixed strategies.

Analyzing Key Game Archetypes

The Prisoner’s Dilemma illustrates a conflict where individual rationality leads to a unique NE that is worse for both players than the cooperative outcome.

The Dilemma highlights the tension between self-interest and the potential for greater collective welfare.

Coordination Games are characterized by having multiple Pure Strategy Nash Equilibria.

These games demonstrate the challenge of equilibrium selection when multiple stable and desirable outcomes exist, requiring external mechanisms for convergence.

Limitations of the Nash Equilibrium

The NE relies on the strong, and often unrealistic, assumption of perfect rationality by all players.

It also assumes common knowledge of rationality (CKR), where players know that their opponents are rational, and so on.

The existence of multiple NEs limits the concept’s predictive power as it doesn’t specify which stable outcome will occur.

Behavioral factors and real-world cognitive constraints often lead actual player choices to deviate from the theoretical NE.

Use Nash Equilibrium to predict competitive market moves.

Model Competitor Actions: Create a simple $2 \times 2$ payoff matrix mapping your firm’s actions against a key competitor’s actions.

Map Payoffs to Metrics: Define payoffs using relevant business metrics like profit margin, market share, or revenue.

Identify Best Responses: Determine your firm’s optimal action (best response) for each of your competitor’s possible strategies.

Locate the Intersection: Find the point (the Nash Equilibrium) where both firms are simultaneously playing their best response to the other’s choice.

Predict Stable Behavior: Use the NE to predict the stable pricing, advertising, or product development strategy that both firms will likely settle upon.

Answer of the day

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, what is the action profile where neither player wants to unilaterally deviate?

Both Defect (Defect, Defect).

The outcome of (Defect, Defect) is the unique Pure Strategy Nash Equilibrium. At this point, if Player 1 chooses to deviate (Cooperate), their payoff worsens. The same is true for Player 2. Therefore, neither player has an incentive to change their strategy, making it a stable outcome.

That’s A Wrap!

Want to take a break? You can unsubscribe anytime by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of your email.