Game Theory: Foundations and Representation

Defining the Game: Understanding players, actions, payoffs, and the structural differences between matrix and tree representations.

Happy Monday!

Insight Trunk is a free lifetime library—a modern replacement for outdated encyclopedias. From Monday to Saturday, we deliver a 10-minute read on a specific subject, with fresh topics each week. Two years later, we revisit each theme with updated insights from our archives—so you’ll never miss a thing. You can unsubscribe anytime using the link at the bottom of this newsletter.

Today, we establish the core vocabulary. We’ll define a game using players, actions, outcomes, and payoffs. Next, we’ll see how to visualize these using Normal-Form (matrix) and Extensive-Form (tree) representations, setting the stage for analyzing strategic decisions.

🧑💻 In this week’s edition: Game Theory

Monday - Foundations and Representation

Tuesday - Solving Simultaneous Games

Wednesday - Solving Sequential Games

Thursday - Games with Incomplete Information

Friday - Dynamic and Repeated Games

Saturday - Key Applications and Concepts

Question of the day

When players choose their actions at the same time, what is the most common representation used for the game?

Let’s find out !

Foundations and Representation

Let’s break it down in today discussion:

Defining the Core Elements of a Game

Structuring the Game: Normal-Form and Extensive-Form

Finding Advantage: Dominant and Dominated Strategies

Timing is Everything: Sequential Versus Simultaneous Moves

Read Time : 10 minutes

🎯 Defining the Core Elements of a Game

The formal analysis of any strategic interaction begins with precisely defining its fundamental components. A game, in this context, is a mathematical representation of a conflict or cooperation scenario. This representation requires four essential elements to be explicitly specified.

Firstly, the players (or agents) are the individuals or entities making decisions within the game. Secondly, the set of available actions (often termed strategies) must be identified for each player. These are the choices a player can make. Thirdly, the collective choices made by all players result in a specific outcome. For instance, in a simple market entry game, the players are the firms, the actions are “Enter” or “Do Not Enter,” and the outcome is the resulting market structure (e.g., monopoly or duopoly).

Finally, and most critically, associated with every possible outcome is a payoff, which represents the utility or welfare level each player derives from that outcome. Payoffs are typically expressed as numerical values. These values encapsulate all the objectives of the players, such as profit, market share, or satisfaction. A rational player is assumed to choose actions that maximize their expected payoff. This payoff structure forms the basis for all subsequent analysis of strategic choice.

Watch this video to explore the basic of game theory in more detail.

📐 Structuring the Game: Normal-Form and Extensive-Form

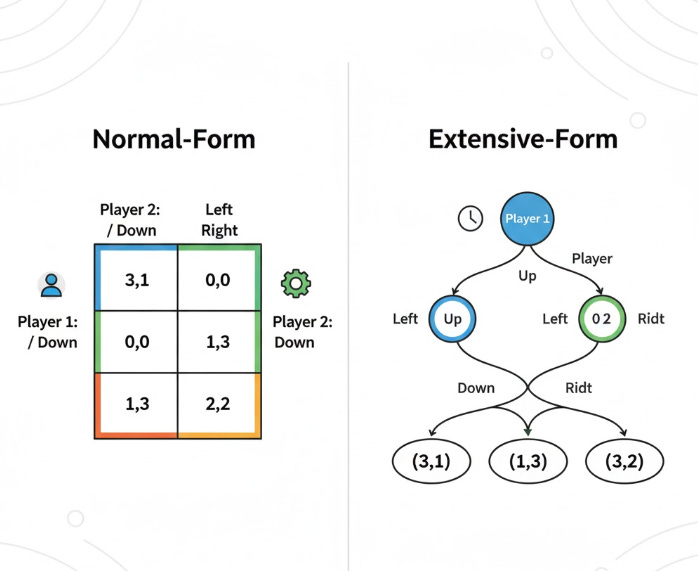

The structural representation of a game is essential for systematic analysis. Game theory employs two principal frameworks: the Normal-Form and the Extensive-Form. These structures are chosen based on the timing and sequencing of the players’ decisions.

The Normal-Form game is typically depicted as a payoff matrix. This structure is the analytical standard for games where all players choose their actions simultaneously, or without knowledge of the other players’ choices. The matrix systematically maps every possible combination of strategies to the resulting payoffs for each player. For example, the classic 2 x 2 Prisoner’s Dilemma is always presented in Normal-Form, clearly showing the outcomes when both “Cooperate” or both “Defect” .

In contrast, the Extensive-Form game utilizes a game tree . This structure is imperative for analyzing sequential-move games, where players alternate turns and have knowledge of prior actions. The nodes on the tree represent decision points, and the branches represent the possible actions. This graphical representation clearly illustrates the dynamic, turn-by-turn nature of strategic interaction, allowing for the analysis of concepts like perfect information and subgames.

The selection between these two forms is driven by the game’s timing structure. Simultaneous games necessitate the comprehensive, static overview provided by the Normal-Form matrix, while sequential games require the dynamic, path-dependent illustration of the Extensive-Form tree.

Get a deeper understanding with this video.

💡 Finding Advantage: Dominant and Dominated Strategies

A fundamental objective in solving games is identifying strategies that are inherently superior or inferior for a player, regardless of the opponents’ choices. This approach allows for preliminary simplification of the game space.

A strategy is deemed dominant if it yields a strictly greater payoff than any other available strategy for a player, irrespective of the strategies chosen by all other players. A rational player will always select their dominant strategy if one exists. For instance, in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, “Defect” is the dominant strategy for both players, as it offers a higher payoff whether the opponent cooperates or defects. The existence of a dominant strategy equilibrium simplifies the solution process significantly.

Conversely, a strategy is dominated if there exists another strategy that consistently yields a strictly lower payoff, regardless of the opponents’ actions. A rational player will never choose a dominated strategy. The process of eliminating these strategies, known as Iterated Elimination of Dominated Strategies (IEDS), is a powerful tool. By removing choices no rational player would ever make, IEDS can often reduce a complex payoff matrix to a single, identifiable outcome, even when a pure dominant strategy equilibrium is absent.

The concepts of dominant and dominated strategies hinge upon the assumption of player rationality. Since rational players always seek to maximize their own payoffs, they will naturally gravitate toward dominant strategies and strictly avoid dominated ones, providing a straightforward pathway for predicting strategic behavior.

Watch this video to expand your knowledge.

⏱️ Timing is Everything: Sequential Versus Simultaneous Moves

The temporal structure of decision-making is a critical differentiator in game theory, leading to distinct analytical methodologies. The core distinction lies in whether players are aware of each other’s choices before making their own.

In simultaneous-move games, players choose their actions concurrently, or at least without observing the choices of their rivals. Examples include sealed-bid auctions or the initial decisions in Cournot competition. Since there is no information about prior moves, these games are best analyzed using the static Normal-Form (matrix) representation. The focus here is on anticipating what others will do based on mutual rationality, as no direct observation is possible.

Sequential-move games involve an ordered process where players take turns, and subsequent players observe the actions of those preceding them. Classic examples include Chess, negotiation, or Stackelberg competition. This structure introduces concepts like commitment and signaling. Because of the dependency on the history of moves, these games necessitate the dynamic, path-dependent structure of the Extensive-Form (game tree) for proper analysis .

The difference in timing dictates the solution concept. Simultaneous games are solved using methods like Nash Equilibrium, while sequential games, due to the observed moves, require the more refined concept of Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium (SPNE), which relies on backward induction to ensure credibility throughout the game’s duration.

Summary

Defining the Core Game Components

A game is a formal model requiring players (decision-makers) and their available actions (strategies).

The combination of all players’ chosen actions determines the resulting outcome of the interaction.

Every outcome is assigned a payoff (utility/welfare) for each player, which they aim to maximize.

Understanding these four elements is the crucial starting point for any game-theoretic analysis.

Structuring the Game for Analysis

The Normal-Form uses a payoff matrix (table) to represent games with simultaneous decision-making.

The matrix systematically lists all strategies and the corresponding payoffs for every outcome.

The Extensive-Form utilizes a game tree to model sequential interactions over time.

The tree shows the order of moves, decision points, and information flow between players.

Identifying Self-Evident Strategies

A dominant strategy is one that always yields the highest payoff for a player, regardless of opponents’ actions.

A rational player will always select their dominant strategy if one exists.

A dominated strategy always yields a strictly lower payoff than another available strategy.

Iterated Elimination of Dominated Strategies (IEDS) simplifies games by removing these inferior choices.

Distinguishing Game Timing Structures

Simultaneous-move games involve players choosing actions without observing their rivals’ choices.

These non-sequential games are typically analyzed using the static Normal-Form matrix.

Sequential-move games involve players taking turns, with later players observing earlier moves.

These dynamic interactions require the Extensive-Form tree and concepts like backward induction for solution.

Use IEDS to quickly solve simple games.

Identify Payoffs: Clearly list the numerical payoffs for all players within the game matrix.

Find Dominated Strategies: Systematically check if any strategy is strictly inferior to another for one player.

Eliminate Inferior Choices: Rationally cross out any dominated row or column from the payoff matrix.

Repeat the Simplification: Apply the elimination process again to the remaining, smaller matrix for the other player.

Determine the Outcome: Continue iterating until a single action combination (cell) remains as the predicted solution.

Answer of the day

When players choose their actions at the same time, what is the most common representation used for the game?

Normal-Form Matrix (or Payoff Matrix).

The Normal-Form representation, often called a payoff matrix , is specifically designed for simultaneous-move games. It clearly lists all players, their possible actions (strategies), and the resulting payoffs for every combination of actions in a compact table format.

That’s A Wrap!

Want to take a break? You can unsubscribe anytime by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of your email.