Game Theory: Dynamic and Repeated Games

Sustaining Cooperation: Analyzing how repeated interaction enables players to achieve better outcomes through history-dependent strategies.

Happy Friday!

Insight Trunk is a free lifetime library—a modern replacement for outdated encyclopedias. From Monday to Saturday, we deliver a 10-minute read on a specific subject, with fresh topics each week. Two years later, we revisit each theme with updated insights from our archives—so you’ll never miss a thing. You can unsubscribe anytime using the link at the bottom of this newsletter.

Today’s focus is on games played over time. We define the repeated game framework, examining how finite vs. infinite repetition changes strategy. We’ll introduce sustaining cooperation using trigger strategies and explore the far-reaching possibilities described by the Folk Theorems.

🧑💻 In this week’s edition: Game Theory

Monday - Foundations and Representation

Tuesday - Solving Simultaneous Games

Wednesday - Solving Sequential Games

Thursday - Games with Incomplete Information

Friday - Dynamic and Repeated Games

Saturday - Key Applications and Concepts

Question of the day

What strategy sustains cooperation in an infinitely repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma?

Let’s find out !

Dynamic and Repeated Games

Let’s break it down in today discussion:

Defining Repeated Games and Their Supergame

Analyzing Finite vs. Infinite Repetition Effects

Learning About Trigger and Grim-Trigger Strategies

Introducing Folk Theorems Regarding Possible Outcomes

Read Time : 10 minutes

🔄 Defining Repeated Games and Their Supergame

The concept of a repeated game provides a framework for analyzing how strategic interactions evolve when players meet and play the same simple game multiple times. This dynamic setting introduces intertemporal dependencies absent in single-shot analysis.

A repeated game is formally defined as the supergame, where the underlying interaction, known as the stage game, is played over a series of time periods, t=1, 2, 3, ... The set of players and the action space remain constant across all periods. The supergame’s rules specify the information structure and the total duration, which fundamentally dictates the strategic possibilities.

Crucially, in a repeated setting, a player’s action in any given period, t, can be conditioned on the history of all actions chosen by all players in all preceding periods, 1, … , t-1. This shared history is the mechanism that links decisions across time. Consequently, a strategy in the supergame is not just a single action, but a complete plan specifying an action for every possible history that might arise at every period.

The final element is the players’ objective function, which is the maximization of the discounted stream of payoffs received across all periods. Future payoffs are discounted by a factor d in [0, 1], where a higher d signifies greater patience. This discounting is vital, as it determines whether the promise of future rewards or the threat of future punishment is sufficient to sustain cooperation that is otherwise impossible in the one-shot stage game.

Get a more thorough explanation in this video.

🔢 Analyzing Finite vs. Infinite Repetition Effects

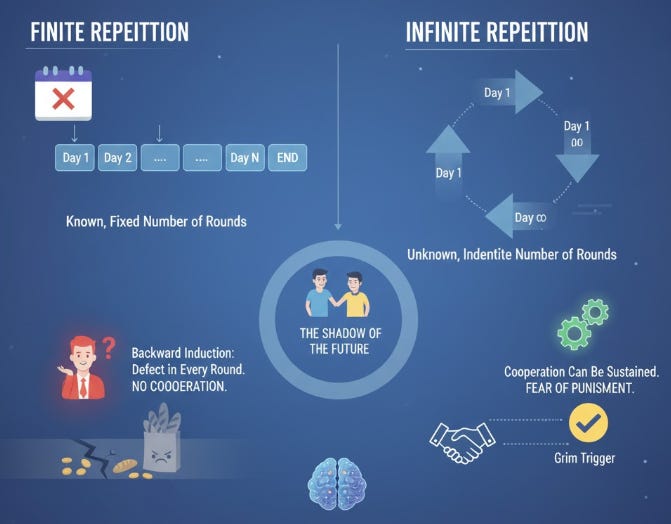

The number of times the stage game is played—specifically, whether the repetition is finite or infinite—is the single most important factor determining the strategic possibilities in a repeated game.

In a finitely repeated game, where the end period is known, the application of backward induction often forces the strategies to collapse. If the stage game has a unique Nash Equilibrium (NE), players know they will play that NE in the final period. Rationality dictates that in the second-to-last period, players anticipate this final outcome and still choose the stage-game NE. This reasoning applies recursively to every preceding period, eliminating the possibility of cooperation throughout the entire sequence, a phenomenon known as the chain-store paradox .

Conversely, infinitely repeated games, or those where the end is uncertain, lack a final period, rendering the backward induction argument invalid. This structural difference introduces the possibility of sustaining cooperative outcomes that are not NEs of the stage game. The absence of a terminal date allows players to credibly threaten perpetual future punishment for any deviation from cooperation.

The stability of these cooperative solutions in infinite games hinges on the players’ discount factor (d). If players are sufficiently patient (d is high), the present value of the stream of future cooperation benefits outweighs the temporary, immediate gain from cheating. Therefore, infinite repetition fundamentally expands the set of enforceable equilibrium outcomes.

This video is your next step to mastering the topic.

🛡️ Learning About Trigger and Grim-Trigger Strategies

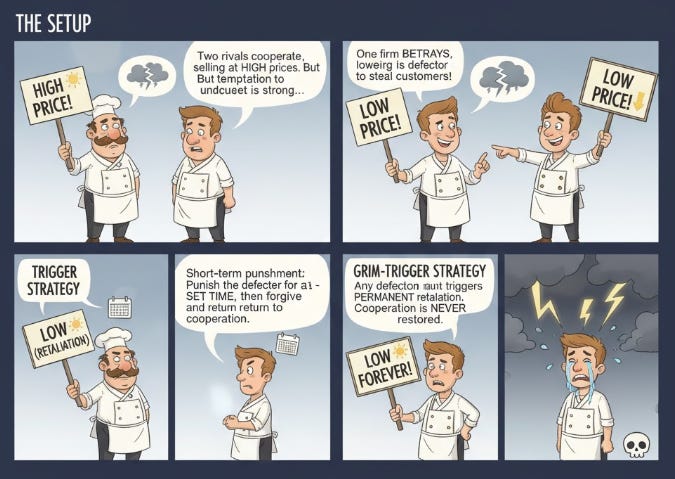

Cooperation in infinitely repeated games is sustained through the credible use of trigger strategies, which are history-dependent strategies that feature a punitive mechanism to deter deviation from cooperative play.

A trigger strategy works by rewarding past cooperation with continued cooperation and punishing any deviation from the agreed-upon path. The critical element is the threat that a single instance of defection from a player will “trigger” a permanent or temporary shift to non-cooperative play by all other players. This creates an immediate cost to cheating that must be weighed against the long-term benefit of sustained cooperation.

The most severe and simple example is the grim-trigger strategy. Under this rule, players cooperate in the first period and continue to cooperate if and only if all players have cooperated in all previous periods. If any player ever defects, the strategy prescribes immediate and permanent defection (i.e., playing the stage-game Nash Equilibrium) by all players forever after. This extreme punishment ensures the short-term gain from cheating is overwhelmed by the infinite loss of future cooperative profits, provided the players are sufficiently patient (high discount factor d).

A milder, but also effective, strategy is Tit-for-Tat, which cooperates in the first period, and in subsequent periods, mimics the opponent’s previous move. This strategy is forgiving, punishing defection only once. The effectiveness of any trigger strategy depends entirely on its credibility and the players’ mutual belief that the punishment will indeed be carried out, as guaranteed by the Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium (SPNE) concept when d is sufficiently high.

Explore additional perspectives about grim trigger strategy by watching this video.

📜 Introducing Folk Theorems Regarding Possible Outcomes

The Folk Theorems collectively represent a set of foundational results in game theory that define the vast range of possible stable outcomes in infinitely repeated games. They fundamentally expand the solution set beyond the stage game’s Nash Equilibrium.

The theorems state that any outcome with an average payoff that is individually rational can be sustained as an equilibrium, provided players are sufficiently patient. A payoff is individually rational if it is at least as high as the player’s minmax payoff—the lowest payoff a player can be forced to accept by the combined actions of the other players, assuming they anticipate the opponent’s strategy. This threshold represents the payoff players can guarantee themselves even in the worst-case scenario.

The critical condition for the Folk Theorems to hold is that the players’ discount factor (d) must be close enough to one. A high d indicates that players value future payoffs almost as much as immediate payoffs. If this patience condition is met, the threat of reverting to the individually rational minmax payoff (which serves as a permanent punishment) is credible enough to deter any short-term deviation from a cooperative path.

The profound implication is that when interactions are ongoing, the strategic constraint shifts from short-run individual incentives to the long-run collective enforcement mechanism. Outcomes that maximize social welfare or lead to high profits, which are unstable in a single period, become viable as Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibria (SPNE) in the supergame. This demonstrates how time and the threat of future consequences can enforce cooperation.

Learn more about the folk theorem what we discussed by watching this video!

Summary

Defining the Repeated Game Structure

A repeated game framework involves playing a single game, called the stage game, multiple times sequentially.

The overall interaction is governed by the supergame rules, which determine duration and information flow.

A player’s strategy must be a full plan, conditioning their current action on the entire history of all past actions.

Players aim to maximize the discounted sum of all future payoffs, weighted by their discount factor (d).

The Impact of Duration (Finite vs. Infinite)

Finitely repeated games usually collapse to playing the stage game’s unique Nash Equilibrium (NE) in every period.

This collapse occurs because backward induction from the final period eliminates all possibilities for cooperation.

Infinitely repeated games (or uncertain termination) remove the final period, thereby blocking the backward induction argument.

This lack of a final date allows players to credibly enforce cooperation through the threat of future punishment.

Strategy Types for Sustaining Cooperation

Trigger strategies are essential for sustaining cooperation; they involve rewarding cooperation and punishing deviation based on past history.

The grim-trigger strategy prescribes cooperation until one player defects, after which all players switch to permanent non-cooperative play.

The effectiveness of these strategies hinges on the players being sufficiently patient (having a high (d)).

These strategies ensure the immediate gain from cheating is outweighed by the present value of the long-term loss of cooperation.

Implications of the Folk Theorems

The Folk Theorems collectively describe the set of possible equilibrium outcomes in infinitely repeated games.

They state that virtually any payoff that is individually rational can be sustained as a Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium (SPNE).

A payoff is individually rational if it is greater than or equal to the player’s worst-case, guaranteed payoff (the minmax payoff).

The theorems demonstrate that time expands the strategic potential, allowing for stable, efficient outcomes that cannot be achieved in a single stage.

Use the discount factor to sustain team cooperation.

Increase the Discount Factor (d): Emphasize long-term career growth or reputation gains to make future team success more valuable now.

Establish Clear Punishments: Define specific, immediate, and credible team consequences for individual behavior that hurts the group goal.

Make Interaction Perpetual: Frame the current project as one in a long series of collaborations to eliminate the “end-game” temptation to cheat.

Design a Grim-Trigger Rule: Agree that any defection will immediately trigger a permanent switch back to a low-cooperation, non-trusting work mode.

Ensure Mutual Observation: Make sure all team members’ actions are transparent so cheating is instantly and reliably detected, which is necessary to trigger punishment.

Answer of the day

What strategy sustains cooperation in an infinitely repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma?

Grim-trigger or similar reward/punishment strategy.

Strategies like the grim-trigger sustain cooperation in repeated games because they promise an immediate and severe punishment (defection forever) if a player ever cheats. If the players are sufficiently patient (have a high enough discount factor), the large future loss from the permanent punishment outweighs the small immediate gain from cheating, making cooperation the stable equilibrium.

That’s A Wrap!

Want to take a break? You can unsubscribe anytime by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of your email.