Critical Thinking: Recognizing Logical Fallacies

Defending reason: Identifying flawed and deceptive argument patterns to maintain logical integrity.

Happy Friday!

Insight Trunk is a free lifetime library—a modern replacement for outdated encyclopedias. From Monday to Saturday, we deliver a 10-minute read on a specific subject, with fresh topics each week. Two years later, we revisit each theme with updated insights from our archives—so you’ll never miss a thing. You can unsubscribe anytime using the link at the bottom of this newsletter.

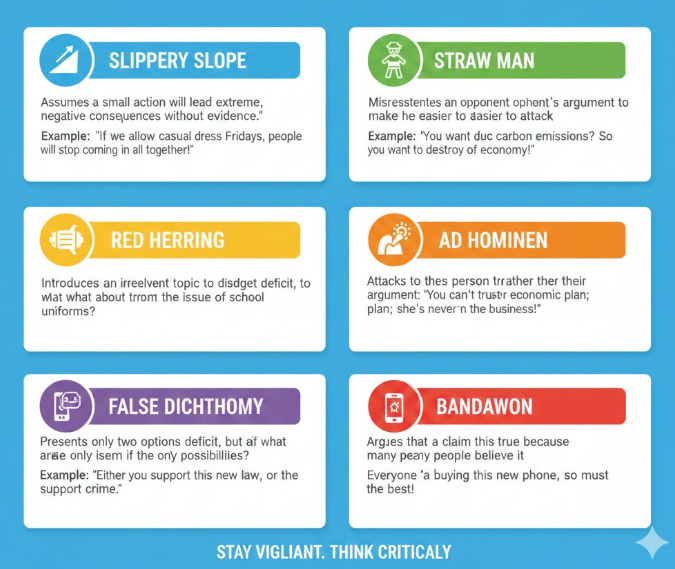

Today is about defense against poor reasoning. We will learn to spot common deceptive patterns like Ad Hominem and Straw Man in arguments, identify diversion tactics like Red Herring, and ensure you avoid committing these errors yourself.

🧑💻 In this week’s edition: Critical Thinking

Monday - Foundation and Definitions

Tuesday - Analysis and Interpretation

Wednesday - Inference and Evaluation

Thursday - Problem Solving and Argumentation

Friday - Recognizing Logical Fallacies

Saturday - Application and Practice

Question of the day

What is the fundamental flaw when an arguer uses the Ad Hominem fallacy?

Let’s find out !

Recognizing Logical Fallacies

Let’s break it down in today discussion:

Learning Common Deceptive Argument Patterns

Identifying Ad Hominem and Straw Man

Spotting Red Herring and Appeal to Emotion

Avoiding Committing Fallacies in Your Reasoning

Read Time : 10 minutes

🛡️ Learning Common Deceptive Argument Patterns

Logical fallacies represent systemic errors in reasoning that vitiate the logical validity and intellectual soundness of an argument. They are not merely factual inaccuracies but structural flaws that render the conclusion unjustified, regardless of the truth of the premises. Understanding these patterns is a foundational defensive mechanism in critical thinking, allowing one to immediately identify and neutralize flawed persuasive attempts.

Fallacies are generally classified into two primary categories: Fallacies of Relevance and Fallacies of Weak Induction. Fallacies of Relevance occur when the premises, though perhaps psychologically relevant, logically fail to support the conclusion because they address an irrelevant issue. For instance, arguing for a policy solely because a famous person supports it is a fallacy of relevance.

Fallacies of Weak Induction occur when the premises provide some minimal support for the conclusion, but the evidence is insufficient or too weak to warrant acceptance. An example is the Hasty Generalization, where a conclusion about an entire group is drawn from an unrepresentative or very small sample.

By formally classifying and naming these deceptive patterns, the critical thinker gains the intellectual vocabulary necessary to articulate precisely why an argument fails, moving beyond a simple feeling that the reasoning is “wrong.”

Get a more thorough explanation in this video.

🔪 Identifying Ad Hominem and Straw Man

Two of the most prevalent and corrosive fallacies in public discourse are Ad Hominem and Straw Man, both serving to divert attention from the substantive merits of an argument. The Ad Hominem (meaning “against the man”) fallacy is committed when an arguer attempts to refute an opponent’s position by attacking their personal character, circumstances, or motives, rather than the logical content of their claim.

This fallacy is structurally unsound because the validity of a premise is logically independent of the person asserting it. For example, dismissing a proposal for economic reform solely because the proposer has a record of corporate bankruptcy is an Ad Hominem; the proposal’s economic merits must be assessed separately.

The Straw Man fallacy occurs when an opponent’s actual position is deliberately misrepresented, simplified, or exaggerated, creating a distorted “straw man” version that is inherently easier to refute. The arguer then attacks this weaker, fabricated argument and falsely concludes that the opponent’s original, robust argument has been defeated.

By recognizing these two diversionary tactics, the critical thinker maintains focus on the real subject of the debate and avoids being manipulated by attacks on character or distortions of position.

This video is your next step to mastering the topic.

🎣 Spotting Red Herring and Appeal to Emotion

Further compromising the integrity of rational discourse are the fallacies of Red Herring and Appeal to Emotion, which function by substituting genuine evidence with irrelevance or sentiment. A Red Herring is a deliberate diversionary tactic wherein an irrelevant topic is introduced into the argument to shift the focus away from the main issue being debated. The arguer succeeds if the audience becomes preoccupied with the new, tangential issue.

For instance, if a politician is questioned about a failed policy, and they immediately shift the discussion to the historical failings of the previous administration, they are introducing a Red Herring. While the history of the previous administration may be relevant in another context, it is logically irrelevant to the efficacy of the policy currently under scrutiny.

The Appeal to Emotion fallacy occurs when an arguer attempts to manipulate the audience’s feelings—such as pity, fear, or outrage—to secure assent to a conclusion, instead of providing logical support. While stirring emotions can be rhetorically effective, basing a conclusion solely on sentiment is logically unsound.

Recognizing these two distinct fallacies is vital for maintaining intellectual discipline, ensuring that evaluation remains focused on verifiable evidence and logical relationships, rather than being swayed by distraction or sentiment.

Explore additional perspectives by watching this video.

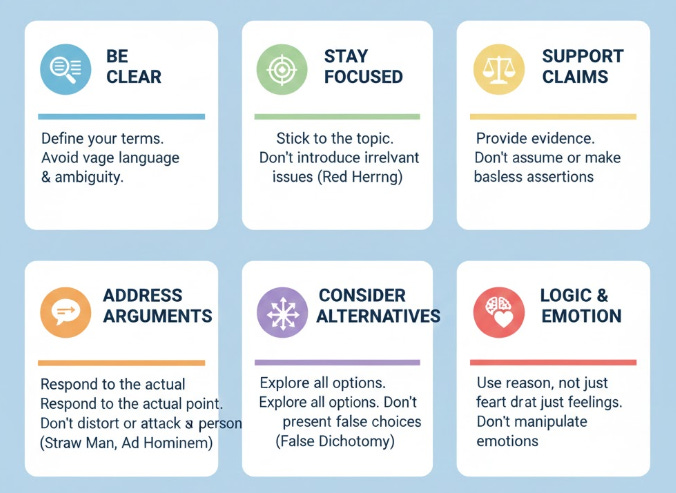

✅ Avoiding Committing Fallacies in Your Reasoning

The final stage of critical engagement with logical fallacies shifts from defense against others’ errors to ensuring the intellectual integrity of one’s own argumentation. Avoiding the commission of fallacies requires rigorous self-monitoring and a deep commitment to intellectual honesty and precision. It is not enough to simply recognize the errors; one must actively prevent their unconscious inclusion in one’s own discourse.

Self-scrutiny involves meticulously checking that every premise used is both directly relevant to the conclusion and factually supported by credible evidence. The arguer must deliberately refrain from relying on convenient but irrelevant appeals, such as attacking opponents’ character (Ad Hominem) or exaggerating opposing views (Straw Man).

For example, when constructing a defense of a policy, the arguer must resist the urge to use fear tactics (Appeal to Emotion) to push acceptance and instead focus exclusively on presenting objective, verifiable data demonstrating the policy’s projected success.

This disciplined approach ensures that the arguments formulated in the constructive phase (Day 4) remain sound and contribute positively to rational public and private deliberation, upholding the highest standards of critical thinking.

Summary

Understanding Flawed Argument Structures

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that undermine an argument’s validity, even if they sound persuasive.

Understanding these patterns is a necessary defensive skill against manipulative communication.

Fallacies are typically categorized as those of relevance (irrelevant premises) or weak induction (insufficient evidence).

Learning the formal names for these errors provides a precise vocabulary to explain why an argument is unsound.

Identifying Character Attacks and Misrepresentation

The Ad Hominem fallacy is a common error where an argument is dismissed by attacking the person making it, not the content.

The logical soundness of a claim is separate from the personal qualities of the person asserting it.

The Straw Man fallacy involves deliberately simplifying or misrepresenting an opponent’s position.

The arguer then refutes the distorted “straw man” version, falsely claiming victory over the original argument.

Spotting Diversion and Emotional Manipulation

The Red Herring fallacy is a deliberate tactic of introducing an irrelevant subject to shift attention away from the original issue.

This tactic attempts to derail rational debate by preoccupying the audience with a tangential subject.

The Appeal to Emotion fallacy attempts to manipulate feelings (e.g., fear, pity) to secure agreement instead of using logical evidence.

Relying solely on emotion as the basis for a conclusion renders the argument logically unsound.

Ensuring Personal Logical Integrity

Mastering fallacies requires rigorous self-scrutiny to ensure one’s own arguments are free from these errors.

The critical thinker must check that every premise is directly relevant and avoids personal attacks or misrepresentations.

Arguments must be based on objective, verifiable data and resist the temptation of emotional manipulation.

This commitment to intellectual integrity ensures that one’s contributions to discourse are sound and ethically presented.

Create a fallacy recognition checklist.

Check for Character Attacks: See if the argument focuses on the person’s character or motives instead of the facts being discussed.

Look for Topic Shifts: Determine if an irrelevant issue is introduced specifically to distract from the original, difficult point.

Verify Position Accuracy: Compare the argument being attacked to the opponent’s actual stated position to spot any distortion.

Isolate Emotional Appeals: Identify if strong feelings (like fear or pity) are being used as a substitute for logical evidence.

Answer of the day

What is the fundamental flaw when an arguer uses the Ad Hominem fallacy?

Ad Hominem attacks the person, not the argument.

The Ad Hominem fallacy attempts to discredit an argument by attacking the character, motive, or other irrelevant trait of the person making it, rather than addressing the argument’s content or evidence. Since the validity of a claim is separate from the person asserting it, this tactic is logically irrelevant and deceptive, undermining rational discourse.

That’s A Wrap!

Want to take a break? You can unsubscribe anytime by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of your email.

The classification into relevance vs weak induction fallacies is a useful framework. What's tricky is that in realworld debates, people often layer multiple fallacies on top of each other, which makes them harder to isolate. Like someone might deploy a red herring that also contains an appeal to emotion, and by the time you've unpacked both, the conversation has moved three topics away. The self-monitoring piece is probably the hardest part tbh. I catch myself reaching for straw man arguments when I'm frustrated because it's so much easier to argue against a simplified version. The gap between knowing what a fallacy is and actually not using it under pressure is way bigger than this checklist suggests.