Critical Thinking: Inference and Evaluation

Moving to judgment: Drawing supported conclusions, determining information gaps, and assessing argument strength.

Happy Wednesday!

Insight Trunk is a free lifetime library—a modern replacement for outdated encyclopedias. From Monday to Saturday, we deliver a 10-minute read on a specific subject, with fresh topics each week. Two years later, we revisit each theme with updated insights from our archives—so you’ll never miss a thing. You can unsubscribe anytime using the link at the bottom of this newsletter.

Today, we move from analysis to judgment. We will learn how to logically draw sound conclusions from evidence, determine what information is still missing, and critically assess the strength and quality of all supporting arguments before reaching a final, justified verdict.

🧑💻 In this week’s edition: Critical Thinking

Monday - Foundation and Definitions

Tuesday - Analysis and Interpretation

Wednesday - Inference and Evaluation

Thursday - Problem Solving and Argumentation

Friday - Recognizing Logical Fallacies

Saturday - Application and Practice

Question of the day

When evaluating an argument, what is the significance of recognizing a “missing piece” of data?

Let’s find out !

Inference and Evaluation

Let’s break it down in today discussion:

Drawing Logical Conclusions from Evidence

Determining What Information Is Needed

Assessing the Quality of Supporting Arguments

Recognizing Gaps in the Provided Data

Read Time : 10 minutes

💡 Drawing Logical Conclusions from Evidence

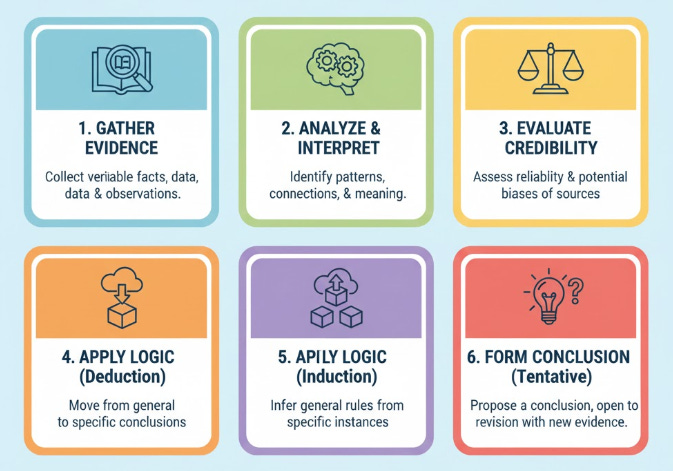

Inference constitutes the intellectual leap from established premises to a justified conclusion. It is the core mechanism by which critical thinking transforms analyzed information into knowledge. This process is fundamentally distinct from mere speculation, as a sound inference is constrained by the evidence and must adhere to strict principles of logic.

A valid inference occurs when the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises; if the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. For instance, if Premise A is “All mammals are warm-blooded,” and Premise B is “A whale is a mammal,” the logical inference must be: “A whale is warm-blooded.” This is an example of deductive reasoning, which guarantees the conclusion’s truth.

Conversely, inductive reasoning draws conclusions that are probable rather than guaranteed, based on patterns observed in evidence (e.g., observing hundreds of white swans and inferring that “All swans are white”). In both forms, the critical thinker must ensure the inferential link is sound and the conclusion is not an arbitrary jump, but a reasoned deduction.

The rigor of the inference process is paramount; accepting a conclusion that does not logically flow from the evidence is a critical failure in the evaluation stage.

Want to go beyond the basics? This video is a great resource.

❓ Determining What Information Is Needed

A critical evaluation requires more than simply scrutinizing the presented evidence; it necessitates actively determining the completeness of the dataset. This step involves identifying information gaps—pieces of data, contextual variables, or opposing viewpoints that are demonstrably relevant to the argument but have been conspicuously omitted. The failure to include necessary information fundamentally weakens the conclusion.

To execute this, the critical thinker must ask strategic, defining questions: “What metrics are used in similar analyses but are absent here?” or “What would someone on the opposing side present as critical evidence?” For example, if a report argues for increased spending on a project based on its local economic benefits, the missing information gap might be the absence of data regarding its long-term environmental costs.

When significant information gaps are identified, the evaluation must proceed with caution. Any resulting inference or conclusion must be labeled as provisional or tentative. This intellectual caution prevents the premature acceptance of an argument that may be invalidated or substantially altered once the necessary, missing data is acquired and integrated into the analysis.

Thus, determining what is needed defines the scope and limits the certainty of the final judgment, ensuring conclusions are based on sufficiency, not merely presence, of evidence.

For an in-depth look, make sure to watch this video.

🌟 Assessing the Quality of Supporting Arguments

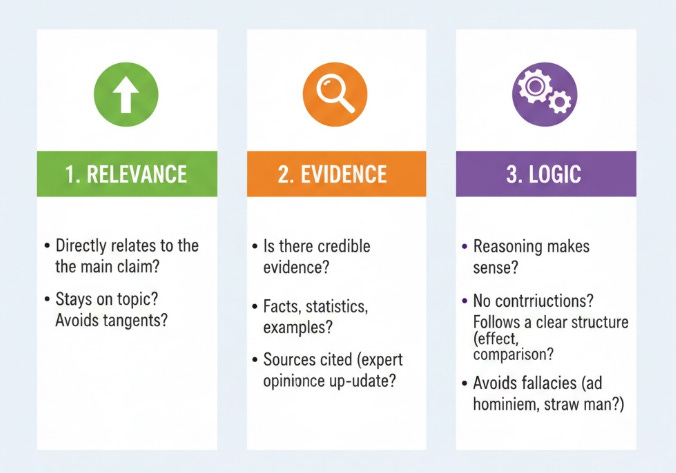

Beyond verifying the factual accuracy of premises, the evaluation stage demands a judgment regarding the overall quality and sufficiency of the supporting arguments. This involves a rigorous assessment of the relationship between the premises and the conclusion they are intended to support. An argument may contain true facts but still be weak if those facts are irrelevant or insufficient to logically warrant the stated conclusion.

Crucial to this assessment is examining the relevance of each premise. Is the evidence presented directly pertinent to the claim, or is it a tangential distraction? Furthermore, sufficiency addresses the quantity and weight of the evidence. For example, a conclusion based on a single, small-scale study is less sufficient than one supported by multiple large-scale, peer-reviewed studies across different populations.

This phase also involves re-evaluating the initial inferences made in Day 2, ensuring that the logical connections between premises are not only valid but also compelling. The arguments must be strong enough, both individually and collectively, to move the judgment beyond mere possibility into the realm of high probability or certainty.

By methodically judging the relevance and sufficiency, the critical thinker avoids being persuaded by arguments that are merely numerous but lack real intellectual substance.

Broaden your understanding by watching this video.

✂️ Recognizing Gaps in the Provided Data

Recognizing specific data gaps is a targeted analytical exercise that focuses on the intrinsic limitations and boundaries of the evidence already provided. It moves beyond simply noting that “something is missing” to defining precisely what type of essential data is absent, thus preventing unjustified generalizations or overstatements of the argument’s scope.

For instance, if a public health argument relies exclusively on quantitative mortality rates (number of deaths), a significant data gap exists if there is no accompanying qualitative data on patient suffering or healthcare access inequalities. The argument is incomplete because it omits the human experience element. Similarly, if research is conducted only within a specific demographic, the absence of data from other groups limits the generalizability of the conclusion.

This critical step also involves scrutinizing the representativeness and scope of the evidence. If an economic study draws conclusions based on data from a highly developed nation, the lack of comparative data from developing economies constitutes a critical gap if the conclusion is intended to be universally applicable.

By meticulously highlighting these specific deficiencies, the critical thinker accurately calibrates the certainty of their conclusion, ensuring it does not exceed what the available evidence can legitimately support.

Summary

The Discipline of Drawing Inferences

Inference is the process of deriving a conclusion from existing premises and evidence.

A logical inference must follow the rules of reasoning, moving beyond what is explicitly stated.

The conclusion should be a reasoned deduction, not an arbitrary speculative leap.

Deductive inferences guarantee the truth of the conclusion if the premises are true.

The critical thinker must ensure the final conclusion is sound and justified by the evidence.

Identifying Essential Missing Information

A crucial evaluative step is actively identifying data and information gaps.

These gaps include missing statistics, necessary contextual details, or absent opposing views.

The presence of significant gaps requires the suspension of a final judgment.

Any conclusion made without this missing information must be labeled as provisional or tentative.

Judging the Strength of Arguments

Evaluation moves past factual verification to assessing the argument’s overall quality and persuasiveness.

This involves meticulously examining the relevance of the premises to the main claim.

The sufficiency of the evidence—its quantity and weight—must be determined.

The logical connections between premises and the conclusion are re-examined for validity and strength.

Recognizing Specific Data Limitations

This is a targeted effort to identify specific deficiencies within the provided evidence.

It involves noting the absence of crucial data types, such as qualitative data missing from a purely quantitative study.

Gaps in representativeness (e.g., lack of comparative regional data) must be highlighted.

Recognizing these limitations prevents the thinker from generalizing or overstating the scope of the conclusion.

Essential reading on logical reasoning.

“Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking” by M. Neil Browne and Stuart M. Keeley: This book provides a user-friendly, question-based framework for evaluating arguments and detecting fallacies.

“Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman: This text details the two systems of thought, offering deep insights into cognitive biases that often undermine sound evaluation.

“A Rulebook for Arguments” by Anthony Weston: This concise guide offers specific rules for constructing and assessing short arguments, focusing on premise-conclusion structure.

“Critical Thinking” by Tom Chatfield: This practical guide introduces tools for navigating information and applying analytical skills to real-world problems and arguments.

Answer of the day

When evaluating an argument, what is the significance of recognizing a “missing piece” of data?

Missing data makes the inference provisional, not final.

Identifying information gaps is vital because a sound conclusion cannot be finalized without complete evidence. When critical data is missing, any inference drawn is only provisional or tentative. Recognizing these gaps prevents the critical thinker from prematurely accepting a conclusion that may be proven false once all relevant information is obtained.

That’s A Wrap!

Want to take a break? You can unsubscribe anytime by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of your email.