Critical Thinking: Analysis and Interpretation

Deconstructing information: Analyzing complex inputs and evaluating the quality of sources and underlying assumptions.

Happy Tuesday!

Insight Trunk is a free lifetime library—a modern replacement for outdated encyclopedias. From Monday to Saturday, we deliver a 10-minute read on a specific subject, with fresh topics each week. Two years later, we revisit each theme with updated insights from our archives—so you’ll never miss a thing. You can unsubscribe anytime using the link at the bottom of this newsletter.

Today, we focus on deconstructing information. Learn how to break down complex arguments, isolate core claims and hidden assumptions, and determine the difference between verifiable facts and mere opinions. Mastering interpretation starts with rigorous analysis of every component.

🧑💻 In this week’s edition: Critical Thinking

Monday - Foundation and Definitions

Tuesday - Analysis and Interpretation

Wednesday - Inference and Evaluation

Thursday - Problem Solving and Argumentation

Friday - Recognizing Logical Fallacies

Saturday - Application and Practice

Question of the day

When analyzing an argument, what specific element often remains unstated but is crucial to identify?

Let’s find out !

Analysis and Interpretation

Let’s break it down in today discussion:

Breaking Down Complex Information Clearly

Identifying Assumptions, Reasons, and Claims

Distinguishing Facts from Subjective Opinions

Evaluating the Source’s Credibility and Bias

Read Time : 10 minutes

🧩 Breaking Down Complex Information Clearly

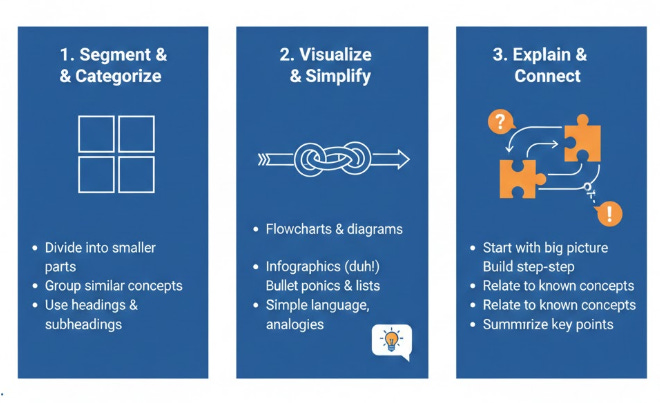

The fundamental operation in critical analysis is the systematic decomposition of intricate discourse, whether written or spoken, into its constituent logical elements. This initial step is paramount because complexity often serves to obscure flawed reasoning or unjustified leaps in logic. The objective is to achieve structural clarity, allowing for an unhindered evaluation of the argument’s validity.

This decomposition requires the meticulous identification of two primary components: the main conclusion and the premises. The main conclusion represents the central claim that the author intends to prove or persuade the audience to accept. The premises, conversely, are the distinct reasons, facts, or pieces of evidence offered explicitly to support that conclusion.

For instance, in an article advocating for a shift to remote work, the conclusion might be “All companies should adopt a hybrid work model.” The premises would then be the specific reasons provided, such as “Productivity has demonstrably increased by 15%,” and “Overhead costs were reduced by 25%.” Isolating these elements prevents cognitive overload and ensures that the focus remains solely on the logical support structure.

By methodically separating the “what” (conclusion) from the “why” (premises), the critical thinker can prepare the argument for subsequent scrutiny and evaluation.

Learn more about what we discussed by watching this video!

🔎 Identifying Assumptions, Reasons, and Claims

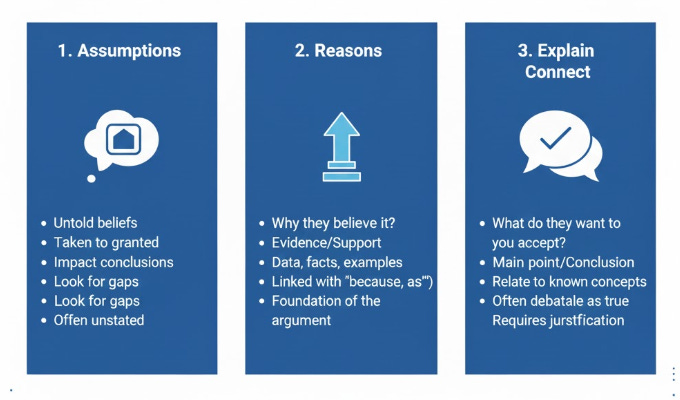

A sophisticated analysis moves beyond merely recognizing the stated conclusion and premises (reasons and claims) to uncovering the argument’s implicit foundations: the assumptions. Reasons and claims are the explicit, declarative statements used by the arguer to build their case. For instance, a claim might be: “The new transit line will reduce traffic congestion,” supported by the reason: “The line offers a faster commuting option.”

However, the argument fundamentally relies on one or more unstated assumptions. These are the beliefs or propositions that the arguer takes for granted as true, but which are not explicitly defended. They function as necessary, yet invisible, links between the reasons and the conclusion. Identifying them is paramount, as a flawed or unproven assumption invalidates the entire logical structure.

Consider the transit example: a crucial assumption might be, “A significant number of current drivers will voluntarily switch to using the new transit line.” If this assumption is proven false (e.g., if drivers find the transit stops inconvenient), the entire argument, despite its strong-sounding claims and reasons, collapses.

Therefore, the critical thinker must constantly question, “What else must be true for this reason to logically lead to this conclusion?” By systematically exposing these hidden premises, the complete veracity of the argument can be assessed accurately.

For a deeper understanding, check out this video.

📊 Distinguishing Facts from Subjective Opinions

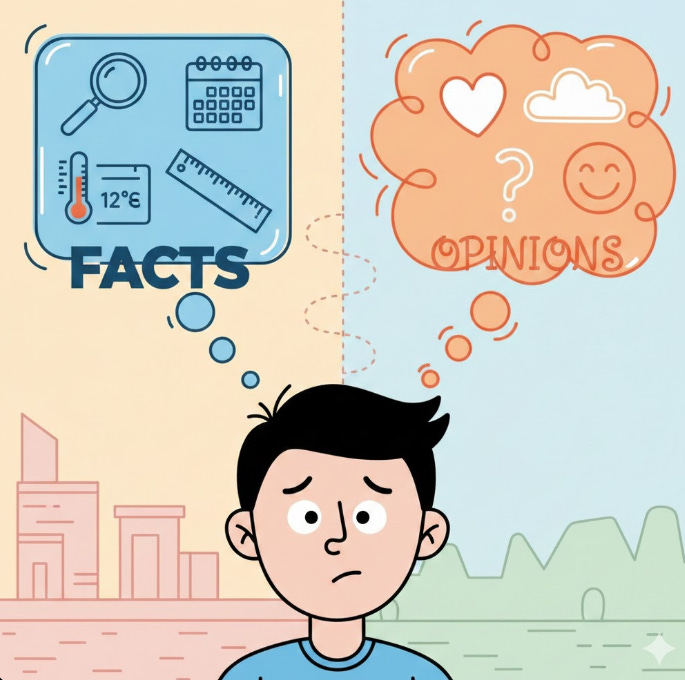

A critical prerequisite for sound evaluation is the ability to precisely distinguish statements of objective fact from expressions of subjective opinion. A fact is an assertion about reality that can be verified as true or false through external, empirical measurement, observation, or reliable documentation. For instance, the statement, “The national unemployment rate is 4.5%,” is a fact, provided the data source is accurate.

Conversely, an opinion is a personal judgment, valuation, or preference that reflects an individual’s feelings or beliefs and cannot be objectively verified or disproven. While opinions can be informed or uninformed, they inherently lack the verifiable basis of factual statements. The assertion, “A 4.5% unemployment rate is excellent,” is an opinion because the definition of “excellent” is subjective and dependent on economic values.

Critical thinking demands that we assign evidential weight exclusively to factual statements. Introducing subjective opinions into the structure of an argument as if they were factual premises constitutes a major logical error.

Therefore, the analyst must scrutinize the language used, noting key indicators: factual claims often use quantitative or verifiable terms, whereas opinions frequently employ evaluative adjectives (e.g., good, bad, should, better). This discernment ensures that evaluation proceeds using reliable, verifiable data.

This video will give you further insights into the topic.

🛡️ Evaluating the Source’s Credibility and Bias

The structural integrity of an argument is directly tied to the reliability of its information sources. A core component of analysis involves the rigorous assessment of a source’s credibility. This requires examining the source’s qualifications, such as relevant education, professional experience, and established reputation within the field. Furthermore, the methodology used to generate the data (e.g., rigorous scientific protocols versus anecdotal observation) is a key indicator of its trustworthiness.

Equally important is the identification of bias, which is any inherent leaning or prejudice that may compromise a source’s objectivity. Bias can manifest in various ways, from overt political or financial interests (e.g., a report funded by an industry group) to unconscious selection bias in research design. The critical question must always be: Does the source have a vested interest in a particular outcome?

A source that lacks expertise or displays evident bias must be treated with extreme caution, as its conclusions may be skewed or manipulated, regardless of whether the individual facts cited are technically correct. The analyst must consider the source’s track record for fairness, accuracy, and completeness when integrating its information.

By systematically scrutinizing both the source’s competence and potential motivations, the critical thinker safeguards the evaluation process against unreliable or slanted foundational evidence.

Learn more about what we discussed by watching this video!

Summary

The Process of Deconstructing Arguments

The initial task is to systematically break down complex arguments into smaller parts.

This involves clearly separating the main conclusion from the premises (supporting reasons).

Establishing structural clarity is crucial for identifying potentially masked weak reasoning.

Understanding this structure prevents the analyst from being overwhelmed by complexity.

The Crucial Role of Assumptions

The analysis must focus on identifying explicit reasons, claims, and implicit assumptions.

Assumptions are unstated beliefs that the arguer takes as true without providing evidence.

If a critical unstated assumption is flawed, the entire argument’s validity collapses.

The critical thinker must proactively determine what else must be true for the argument to hold.

Differentiating Evidence Types

A fundamental analytical skill is distinguishing objectively verifiable facts from subjective opinions.

Facts can be proven true or false using empirical data or external verification.

Opinions are personal judgments or value statements that lack objective proof.

Only factual premises should be given substantial evidential weight in logical discourse.

Vetting the Source for Trustworthiness

The quality of the argument relies heavily on the source’s credibility.

Credibility is assessed by reviewing the source’s expertise, qualifications, and methodology.

Bias (political or financial leaning) must be identified as it compromises objectivity.

A source with poor credibility or high bias makes even accurate facts questionable within the argument’s context.

Reverse-engineer the argument chain.

Start with the Conclusion: Begin by clearly stating the central point the argument is trying to prove, working backward from the end result.

Isolate the Premises: Identify the one or two main reasons offered immediately before the conclusion that are meant to provide direct support.

Locate the Assumptions: For each premise, ask what unstated idea must be accepted as true for that premise to logically connect to the conclusion.

Question the Evidence: Once the chain is exposed, ask if the evidence supporting the premises is factual and comes from a credible, unbiased source.

Answer of the day

When analyzing an argument, what specific element often remains unstated but is crucial to identify?

The unstated assumptions are crucial to identify.

Assumptions are premises or beliefs that an arguer takes for granted without explicitly stating them. Identifying these hidden foundations is critical because if an unstated assumption is false or illogical, the entire argument built upon it becomes invalid, regardless of how strong the stated evidence appears.

That’s A Wrap!

Want to take a break? You can unsubscribe anytime by clicking “unsubscribe” at the bottom of your email.